Chatter Stability with Orthogonal Rotation

Requires a Wolfram Notebook System

Interact on desktop, mobile and cloud with the free Wolfram Player or other Wolfram Language products.

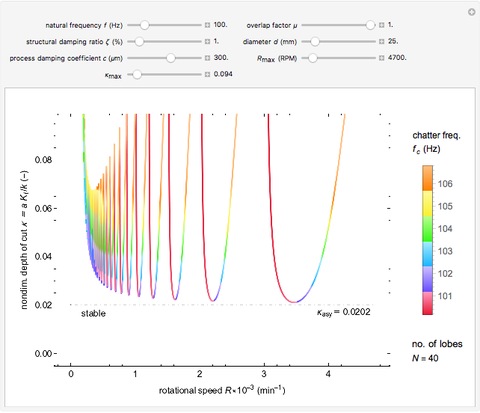

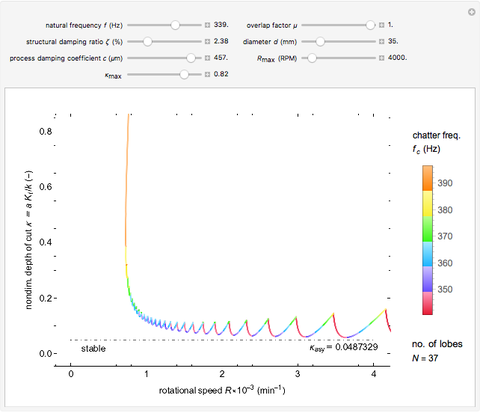

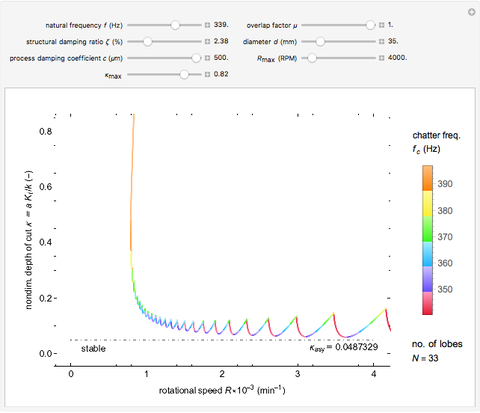

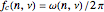

The classical model of regenerative chatter is a simple harmonic oscillator excited by a vibration-dependent force with constant delay. This results in a delay-differential equation whose stability analysis gives rise to a chart demarcating the nondimensionalized depth-of-cut  and the rotational speed

and the rotational speed  . The well-developed theory available in [1, 2] is adapted for a general overlap factor

. The well-developed theory available in [1, 2] is adapted for a general overlap factor  and process damping

and process damping  . This Demonstration studies the effect of natural frequency

. This Demonstration studies the effect of natural frequency  and structural damping ratio

and structural damping ratio  on the

on the  -

- space and chatter frequency

space and chatter frequency  at the threshold of stability. Process damping is important at low rotational speeds and high lobe numbers, where the lobed borderline of stability is completely separated from the asymptotic borderline.

at the threshold of stability. Process damping is important at low rotational speeds and high lobe numbers, where the lobed borderline of stability is completely separated from the asymptotic borderline.

Contributed by: Raja Kountanya (May 2014)

Open content licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Snapshots

Details

Chatter vibration in machining processes is an extremely complex phenomenon; field troubleshooting relies on rigorous data collection and diagnosis by specialists. It also entails expensive downtime and high scrap costs. Chatter is a well-known case of self-excited regenerative vibration, where energy is extracted from the machining process itself. This Demonstration provides a basic insight into the simplest case, that of orthogonal turning. Here, a useful output of the theoretical analysis is the stability chart that demarcates the space of depth of cut and rotational speed into stable and unstable regimes. The stability chart is constructed through a sequence of lobes, each of which prescribes an unstable region.

How the tool and the workpiece interact is modeled as a single-degree-of-freedom system with given resonance frequency  and damping ratio

and damping ratio  . The cutting stiffness is the force per unit of uncut chip thickness. The nondimensionalized depth of cut

. The cutting stiffness is the force per unit of uncut chip thickness. The nondimensionalized depth of cut  is defined as the ratio of the cutting stiffness to the machine stiffness. With

is defined as the ratio of the cutting stiffness to the machine stiffness. With  as the depth of cut,

as the depth of cut,  as the specific energy, and

as the specific energy, and  as the structural stiffness,

as the structural stiffness,  is given by

is given by  . In the literature,

. In the literature,  is sometimes referred to as the stiffness ratio.

is sometimes referred to as the stiffness ratio.

Process damping [1, 2] refers to energy dissipation by the rubbing of the tool flank on the wavy workpiece surface. It is significant at low rotational speeds with a high lobe number. If ignored, the deduced stability chart conflicts with the shop practice of reducing rotational speed to eliminate chatter. That is, if the process is unstable at a higher rotational speed, without process damping, it is necessarily unstable at a lower speed. Another important consideration is the overlap factor, usually assumed to be unity in the literature, that captures the influence of vibration position in the previous rotation.

The workpiece, rotating at a constant rate of  rotations per minute, takes the time duration

rotations per minute, takes the time duration  to complete one rotation. Therefore,

to complete one rotation. Therefore,  . The vibration of the tool as a function of time is denoted by

. The vibration of the tool as a function of time is denoted by  . With

. With  as the diameter of the workpiece, the cutting speed of the operation is

as the diameter of the workpiece, the cutting speed of the operation is  ;

;  is the overlap factor. Process damping is incorporated through the coefficient

is the overlap factor. Process damping is incorporated through the coefficient  . With reference to Eq. 4.22 in [1],

. With reference to Eq. 4.22 in [1],  . Though

. Though  has the units of length, its relation to the flank wear land length

has the units of length, its relation to the flank wear land length  is reported in [1] to be

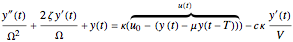

is reported in [1] to be  . The governing differential equation with this nomenclature is then given by

. The governing differential equation with this nomenclature is then given by

.

.

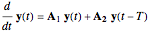

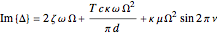

With this formulation, the  -

- space has to be demarcated into stable or unstable regimes. The quantity

space has to be demarcated into stable or unstable regimes. The quantity  can be suitably absorbed into

can be suitably absorbed into  and therefore ignored in the subsequent stability analysis. The state-space method in [3] is a robust way to compute the stability lobes since it employs a free variable

and therefore ignored in the subsequent stability analysis. The state-space method in [3] is a robust way to compute the stability lobes since it employs a free variable  with fixed bounds.

with fixed bounds.

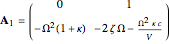

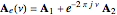

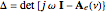

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

.

.

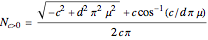

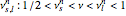

Here, the free variable  ,

,  , is related to the fractional vibrational cycle in one complete rotation of the workpiece and

, is related to the fractional vibrational cycle in one complete rotation of the workpiece and  represents the angular chatter frequency. The real and imaginary parts of

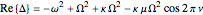

represents the angular chatter frequency. The real and imaginary parts of  are zero at the threshold of stability (TOS). These are given by

are zero at the threshold of stability (TOS). These are given by

,

,

.

.

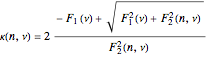

These equations have to be solved simultaneously with  , where

, where  . Each value of

. Each value of  gives rise to a stability lobe. The union of all the unstable zones for each

gives rise to a stability lobe. The union of all the unstable zones for each  gives the complete unstable region in

gives the complete unstable region in  -

- space, the complement of which is the stable region. At TOS,

space, the complement of which is the stable region. At TOS,  is given by

is given by

,

,

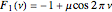

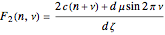

where

,

,

.

.

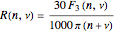

The chatter frequency  and workpiece rotational speed

and workpiece rotational speed  at TOS are given by

at TOS are given by

,

,

,

,

where

and  represents the total number of lobes.

represents the total number of lobes.  when

when  , but when

, but when  ,

,  is finite and given by greatest integer less than

is finite and given by greatest integer less than  , obtained by simultaneous solution of

, obtained by simultaneous solution of  and

and  . Also,

. Also,  is given by

is given by

.

.

The intersections of the lobes can be solved to give the lobed borderline of stability (LBS). The lobes are first restricted to bounds  determined from

determined from  . Then, using root-finding, the bounds

. Then, using root-finding, the bounds  corresponding to the intersection of the

corresponding to the intersection of the  and

and  lobes are found by simultaneous solution of the equations

lobes are found by simultaneous solution of the equations

,

,

.

.

The asymptotic borderline of stability (ABS), governed purely by structural damping, is given by  . The stable region is indicated by the presence of the word "stable". The number of lobes

. The stable region is indicated by the presence of the word "stable". The number of lobes  for given

for given  is also displayed.

is also displayed.

By varying  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , you can study the effect of all the variables. The

, you can study the effect of all the variables. The  and

and  sliders allow rapid zooming in and out to study the stable/unstable regions more closely. The charts have been corroborated with data on p. 139 in [1] and bookmarked in the Demonstration. The chatter frequency at the threshold of stability is shown as a varying color on the LBS. At low

sliders allow rapid zooming in and out to study the stable/unstable regions more closely. The charts have been corroborated with data on p. 139 in [1] and bookmarked in the Demonstration. The chatter frequency at the threshold of stability is shown as a varying color on the LBS. At low  , the LBS curve can be seen to move away from the ABS curve completely due to process damping. Its influence on chatter frequency can also be seen clearly.

, the LBS curve can be seen to move away from the ABS curve completely due to process damping. Its influence on chatter frequency can also be seen clearly.

References

[1] Y. Altintas, Manufacturing Automation: Metal Cutting Mechanics, Machine Tool Vibrations, and CNC Design, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[2] Y. Altintas, M. Eynian, and H. Onozuka, "Identification of Dynamic Cutting Force Coefficients and Chatter Stability with Process Damping," CIRP Annals, 57, 2008 pp. 371–374. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2008.03.048.

[3] S-G. Chen, A. G. Ulsoy, and Y. Koren, "Computational Stability Analysis of Chatter in Turning," Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, 119(4), 1997 pp. 457–460. dx.doi.org/10.1115/1.2831174.

Permanent Citation